Whether staring at a document or an email, all of us have been overcome with puntuation panic before. The cursor blinks while your eyes try to comb through each sentence, but something in your gut isn’t right. That’s when the question finally lands, is there a missing comma? Get a refresher on comma rules you might have forgotten, and avoid the last minute anxiety of questioning your punctuation.

The rules followed in this break down come from the current edition of the Associated Press Style Guide (AP). A few of the more common comma situations have rules set out for the times when the mark isn’t needed. While each style guide has their own set of rules, AP is one of the few widely acknowledged in communication industries.

Let’s dig in.

Introductory comma

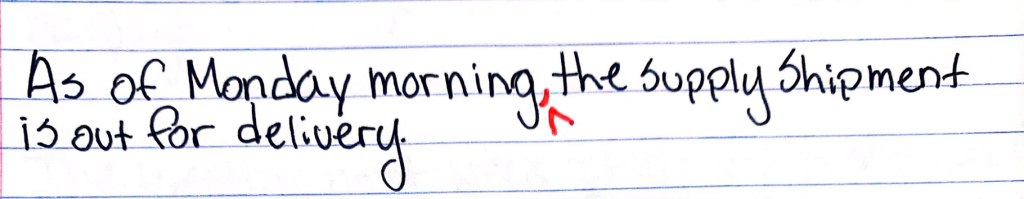

AP Style explains that a comma is put before introductory words or phrases in order to separate them from the main clause of the sentence. While there are exceptions to the rule, the longer you make an introduction to your point then the more likely you require a comma.

Sentence structure like this first example, is a more traditional introduction that you’re likely to see. Not only is the first part of the sentence an introduction phrase but also a dependent clause, meaning it would be best seperated for the sake of clarity.

When you don’t need it

In this case, the introduction is short and blends easily while reading it. With an easy and small introduction you won’t run into any misunderstandings if the comma is out.

Oxford Comma

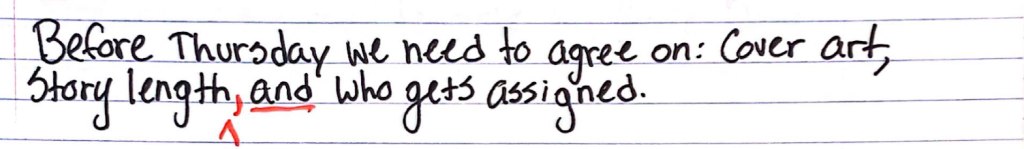

The much debated serial comma, otherwise known as the Oxford comma, is placed before the conjunction that precedes the last item in a series. The most recently updated guideline from AP Style takes a neutral position on this particular debate. If a list is simple and easily understood without the last comma, then there is no need for it. However, if the list could be misunderstood in any way due to a lack of punctuation, then the comma needs to be placed.

Due to the number of elements that make up this particular message, setting the last task apart helps not only clarity, but the intention of these three separate tasks.

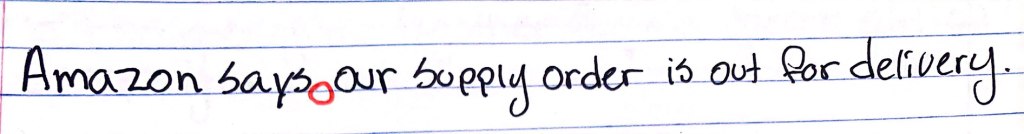

When you don’t need it

An example like the one above is a common argument that many people use as a reason to cut out using the Oxford comma. Yet, it is only convenient in this case of a simple, straight forward list. If you were to take a quick glance at a sentence like this, there is a low possibility of misreading anything.

Conjunction Comma

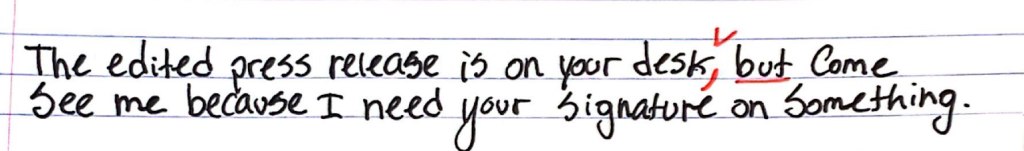

When a conjunction links two independent sentences together, a comma is required to show where that connection happens. Conjunctions are words or phrases that connect all the pieces of a sentence together. The most common conjunction words are: for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so.

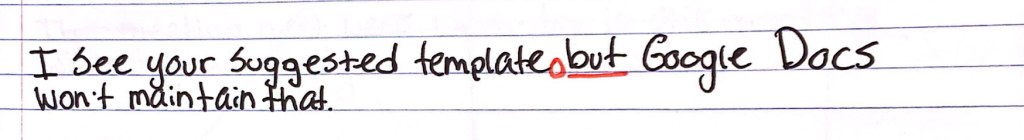

The word but is connecting both sentences that could stand apart on their own. In order to show that such a move is possible, the comma needs to precede the chosen conjunction. With this structure, it allows both thoughts to remain linked without looking like a run-on sentence.

When you don’t need it

In the case where two linked sentences have the same subject, AP Style doesn’t require a comma. Notice in the example above that the conversation remains focused on the template in question. While both thoughts could stand alone as sentences, one is providing context to the other.

Nonessentials Comma

When there is a lot of information put together in a sentence, there are essential clauses that provide vital information, and nonessential clauses which are added pieces. A nonessential clause comma comes in sets, to separate important thoughts from what can be moved aside.

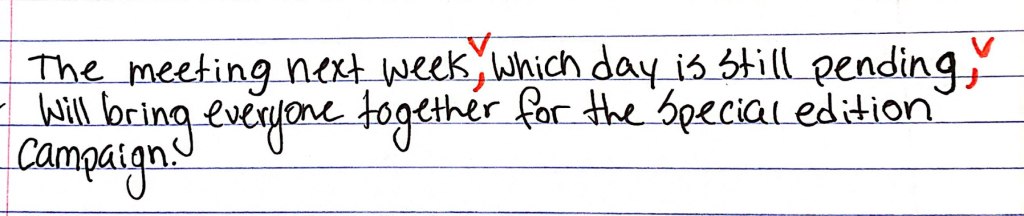

Here the main focus of this sentence is the purpose of the meeting. If the dependent clause which day is still pending were to be lifted out entirely, the sentence would still stand on its own. Nevertheless, if the dependent clause stayed in without the presence of commas, then you have a run-on sentence. Not to mention, there wouldn’t be a way to tell if the focus is on scheduling or the meeting purpose.

Vocative Comma

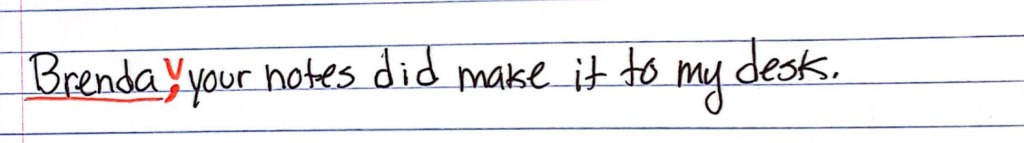

The vocative comma is more commonly called the comma of direct address. Yet, the root of using the vocative comma comes from a grammar tool known as the vocative case. Merrim-Webster defines vocative case as, “marking the one addressed” and that is the exact purpose of this specific comma.

You will most commonly see a direct address comma in statements that are meant to get a specific person’s attention, yes/no answers, or the beginning of emails. Looking over the given example, placement of that comma separates the confirmation from who is directly involved.

Equal Adjectives Comma

The equal adjectives comma happens when a series of adjectives in equal rank are listed. In other terms, the comma is used when multiple adjectives are listed to try and describe a specific thing.

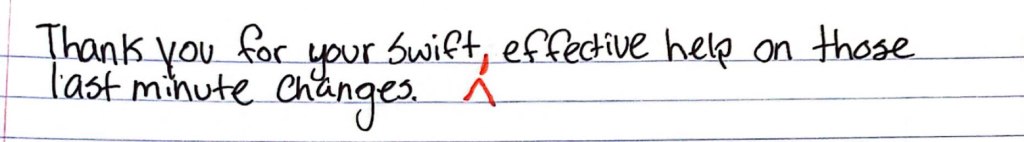

In the example, both words swift and effective are describing the help that was given. There is an acid test to check if your adjectives are of equal rank, insert the word and between your adjectives to see if it changes the meaning of your sentence. For this particular case, inserting the word does nothing. The comma fits.

Duplicate Words Comma

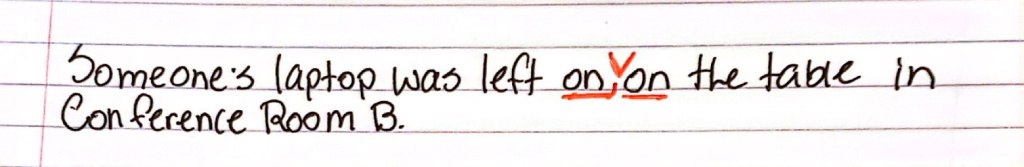

Sometimes a word appears twice in a row with two different meanings. A comma for duplicate words is required in order to show both meanings and that the choice was not a stray typo.

Most of the time duplicates are the simplest of words that take on multiple layers. For this sentence, we have on as in electronic power and on as in located on a surface. Therefore, in order to make that clear to anyone else, the comma needs to stay.

You must be logged in to post a comment.